Article was originally created for Vice Motherboard, which holds distribution rights till Sep 2018.

Rise of parking spaces in Los Angeles

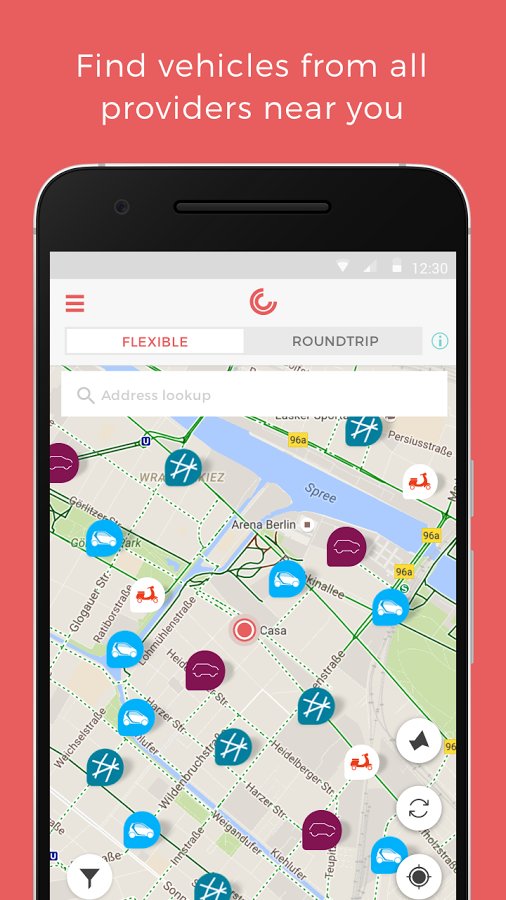

Sometimes the future arrives humbly in our everyday life, until one day we realize its implications. Carsharing is like that—I was ignoring it until I noticed car2go popping around Berlin:

I had tried ZipCar (USA) and Co-wheels (UK) before, but this was different. ZipCars and Co-wheels cars needed to be booked for a few hours and then returned to the same spot. Car2go allowed me to book a car by the minute and leave the car anywhere in the city zone. When I reach my destination, I can park the car anywhere, sometimes using smart parking, to the enormous joy of the parking-seeking SUV owner behind me. When going somewhere in the city, driving back and forth takes less than an hour, so for the rest of the evening, that car2go can be used by other users.

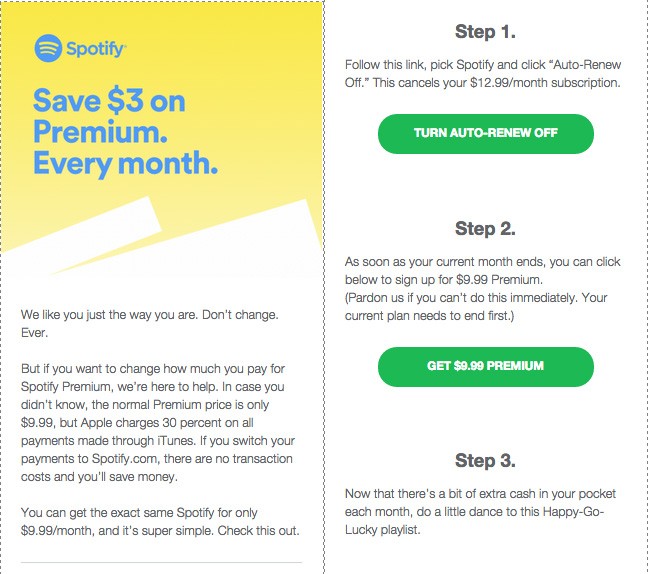

One alternative to carsharing is ridesharing (Uber, Lyft, or similar), but ridesharing is more expensive (you need to pay for a driver) and I will argue that it is just an intermediate step until we have self-driving cars.

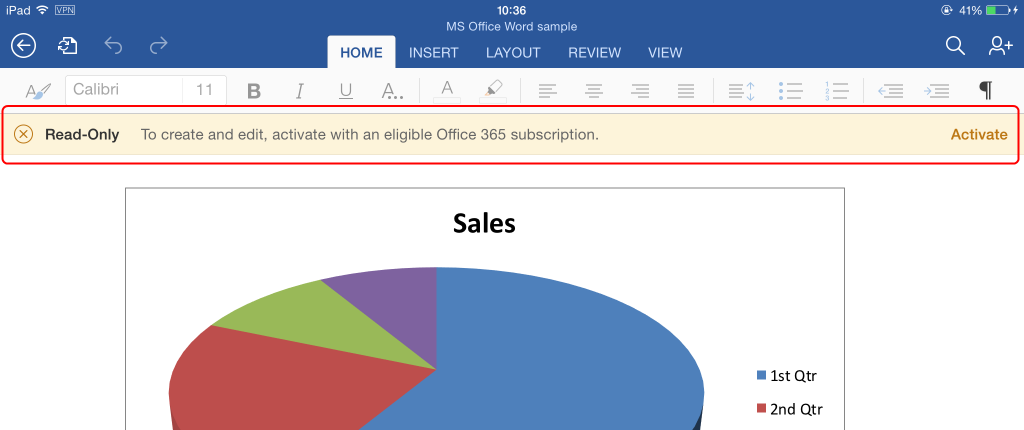

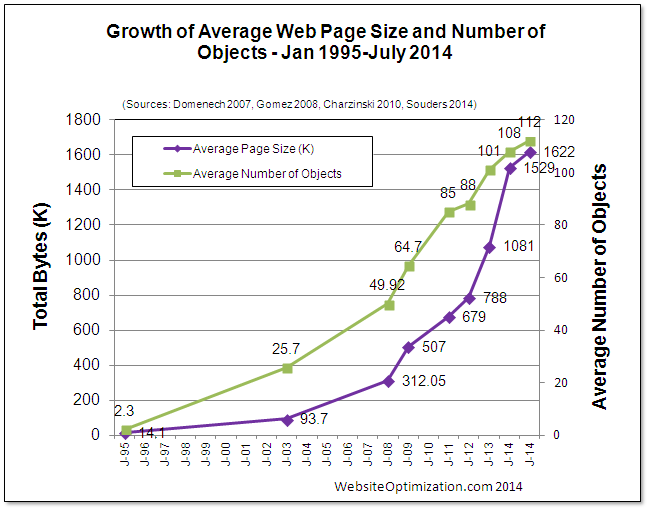

Both carsharing and ridesharing solve the biggest problems of cars in the city: utilization. The average private car spends 95 percent of its time parked somewhere, where it waits faithfully for you to finish with your work, shopping, or a great social time that will make you too intoxicated to operate it.

A death of parking

In comparison, a shared car with 50 percent usage has 10 times better utilization and needs parking only half the time. But, that doesn’t mean that the ideal carsharing city will need half the parking spaces. Surprisingly, carsharing would reduce the number of parking spaces a city needs by more than 10 times.

Let’s calculate for total carsharing (all private cars replaced with shared cars) with 10x better utilization:

| Private car | Shared car (10x) |

| Used | 5% | 10 x 5%

= 50% |

| Parked | 95% | 50% |

| Number of cars in the city | N | N / 10 |

| Parking places needed | N x 95% | (N / 10) x 50%

= N x 5% |

| Parking reduction | — | (N x 95%) / (N x 5%)

= 19x |

Ideally, if shared cars are used 10x more, we need 10x fewer of them to power the city. But since they also spend less time parked, we need 19x fewer parking spaces!

But there is a miscalculation in the above math.

It is questionable whether 50 percent carsharing utilization can be achieved because of rush hours and the suburban commute.

Rush hours mean that most people want to use cars during peak times. Let’s suppose that all people need cars in a three hour peak and that the average non-rush commute lasts for 30 minutes (I will explain later why I’m using a non-rush commute). Then we can only have 6x fewer shared cars to replace private cars, not 10x.

But an even larger problem is the suburban commute—from suburbia to the city in the morning, and the other way round in the afternoon. The first commuter in the morning leaves a shared car in the wrong place—in the city. This is not such a big problem in Berlin, because people live and work in all neighborhoods of the city. But it is a big problem for American cities because of their typical suburban sprawl. Every morning, the number of shared cars in your cul-de-sac should match the number of morning commuters. Maybe that is one reason ZipCar in the US allows one-way trips only with designated cars and only in Boston, LA, and Denver.

Self-driving cars come to the rescue. They could drive you to the city and then come back to pick up the next commuter. This halves the efficiency, but is still better than leaving cars idly parked. As the original 10x utilization was probably too optimistic, let’s recalculate using 6x and 3x:

| Shared car (6x) | Shared car (3x) | Shared self-driving car (3x) |

| Used | 6 x 5%

= 30% | 3 x 5%

= 15% | 3 x 5%

= 15% x 2 = 30% |

| Parked | 70% | 85% | 70% |

| Number of cars in the city | N / 6 | N / 3 | N / 3 |

| Parking places needed | (N / 6) x 70%

= N x 11.7% | (N / 3) x 85%

= N x 28.3% | (N / 3) x 70%

= N x 23.3% |

| Parking reduction | (N x 95%) / (N x 11.7%)

= 8.1x | (N x 95%) / (N x 28.3%)

= 3.4x | (N x 95%) / (N x 23.3%)

= 4.07x |

If everybody commutes from suburbia to the city and utilization is only 3x, the city gets to have 3.4x fewer parking lots, not bad! With self-driving cars, cities can reclaim even more street space. When they are not needed, an army of self-driving cars can drive themselves to multilevel garages or off-city parking.

It gets better. If you have ever bought a private car, you probably did a largest common denominator calculation—what is the longest trip you will need the car for? Because there are two times in a year when you go camping, you commute to your work in a large sedan or SUV. Alone. When picking a shared car, you use the lowest common denominator—the smallest car that will get you to your destination. And two smart cars fit in a single parking space.

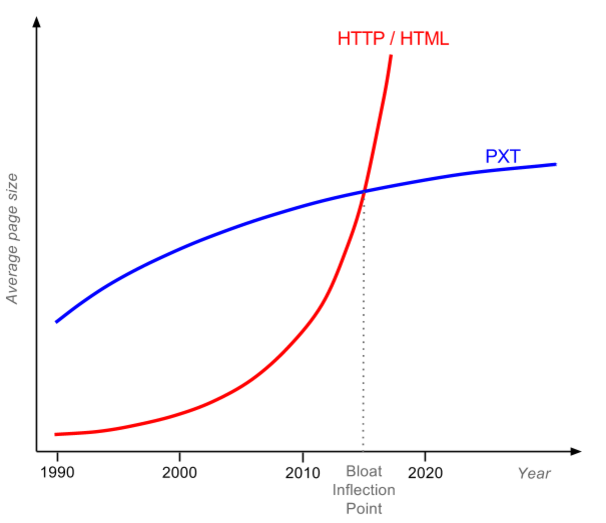

This is a eureka moment for carsharing and self-driving cars. Most people I talk with think the cities of the future will be similar to today, except that you will own an electric self-driving car. In my modest opinion, that is similar to people of the 19th century imagining faster horses.

But wait, there is more

The annihilation of parking lots is just one of the benefits of carsharing:

- Currently, if you use a private car to travel to a destination, you also need to use it to return from a destination. Carsharing cooperates with other modes of transport. Go somewhere with a foldable bicycle, and if it starts to rain, no problem. Book the closest shared car and put the bicycle in the trunk. Go to a bar with a shared car, get tipsy, and book a Lyft ride back home.

- Fewer parked cars means you spend less time looking for parking. Research shows that on average, 30 percent of the cars in congested downtown traffic are cruising for parking.

- You need to walk from your location to the location where you parked a private car. In an ideal carsharing city, you just walk out and take the first shared car available outside.

- Because people are driving smaller shared cars, there is less pollution.

- If you need a van, a truck, or a limousine, you just find and book one using a smartphone.

- Insurance and servicing is handled by the carsharing company, not you. Because they have a huge fleet, they get volume pricing.

- When your car breaks, you don’t need a replacement car. Every carshare you see is your “replacement” car.

- With less need for parking space, through streets can ditch side parking and add two extra traffic lanes.

Not everything about carsharing is perfect. Sometimes the shared car I got wasn’t quite clean—somebody had transported a dog on a passenger seat. But, when I think about it, I didn’t clean my previous private car for months and sometimes it looked like I was transporting pigs with diarrhea, so maybe I shouldn’t complain.

How does the future look now?

Berlin is quite competitive, so we get a small glimpse of the future. Car2go, owned by Daimler AG, originally offered only smart cars. Car2go’s biggest competitor is DriveNow, owned by BMW and Sixt, which offers Minis and BMWs, like this electric i3:

Car2go decided to pimp up its rides, so now you can book a Merc:

Car2go decided to pimp up its rides, so now you can book a Merc:

Citroen also decided to join the party. The company offers a fleet of mostly electric C-Zeros with Multicity:

Citroen also decided to join the party. The company offers a fleet of mostly electric C-Zeros with Multicity:

Volkswagen got angry that Mercedes and BMW were eating all the cake, so it purchased a 60 percent stake of Greenwheels:

Volkswagen got angry that Mercedes and BMW were eating all the cake, so it purchased a 60 percent stake of Greenwheels:

While Sixt is partnering with BMW, Hertz has its own Hertz On Demand, although it is obvious from its website that Hertz is still in rent-a-car mindset and doesn’t understand how the new thing works.

While Sixt is partnering with BMW, Hertz has its own Hertz On Demand, although it is obvious from its website that Hertz is still in rent-a-car mindset and doesn’t understand how the new thing works.

But why stop at cars? Other vehicles have the same problem; you only use them 5 percent of the time. eMio offers the same sharing concept for electric scooters:

Don’t laugh at the idea of shared scooters. This is a cultural thing—while in the US, the ideal transportation vehicle is a sedan and in Europe a compact car, two billion people in Asia consider scooters a family transport solution. Look at this nice family in Vietnam:

Don’t laugh at the idea of shared scooters. This is a cultural thing—while in the US, the ideal transportation vehicle is a sedan and in Europe a compact car, two billion people in Asia consider scooters a family transport solution. Look at this nice family in Vietnam:

And eMio is not the only one. Just last month, Coup launched a fleet of 200 beautifully designed, Gogoro electric shared scooters to Berlin:

And eMio is not the only one. Just last month, Coup launched a fleet of 200 beautifully designed, Gogoro electric shared scooters to Berlin:

Both Coup and eMio have an unusual charging solution: their teams go around the city and swap empty batteries for full ones.

Both Coup and eMio have an unusual charging solution: their teams go around the city and swap empty batteries for full ones.

Other carsharing companies have “socially automated” refueling. For example, in car2go you don’t ever have to refuel, but they give you 10 free minutes if you fill up a car with less than a quarter of a tank of gas.

Prices are already reasonable. In my experience, car2go smart is half the price of Uber in Berlin (which is not the real Uber, to be honest). But it can go lower with better utilization and economies of scale.

Finally, tourists can rent a NextBike bicycle from 1€ per 30 min.

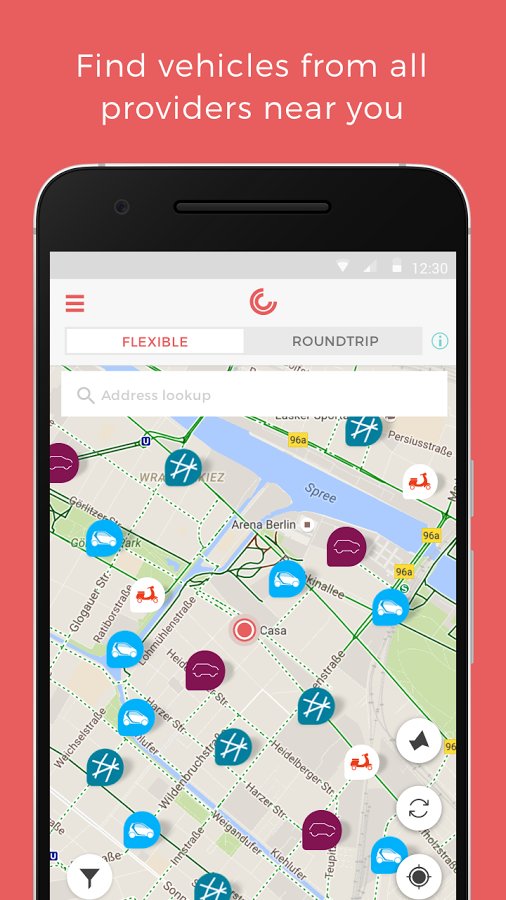

As you can see, the situation is quite complicated here, and I know what some entrepreneurial readers are thinking. But hold your breath, as there is already an app that displays all of the above on the same map:

Death of traffic jams (and birth of queues)

More radical changes will happen when shared cars become a majority in the city.

Total carsharing can eliminate the traffic jams of rush hour—but that doesn’t mean you

won’t have to wait.

Why does a traffic jam happen, anyway? All people jump into their private cars at once and decide to drive along a similar route. Main routes have limited throughput, so you end up queueing on junctions and on the highway. The queue just makes things worse, as it lowers car throughput. It is an expensive system in which you line up in a running car, waiting for your turn. In total carsharing, that can’t happen. Since there are 3x or 6x fewer cars available, there is no way that everybody can just jump in a car and go. Now you don’t wait on a highway, you wait for your turn to get a shared car. I would argue argue that this is better because:

- You are going to wait in your home or office (for a car to become available), not on the highway.

- There is less chance of some route “jamming” and reducing car throughput.

But waiting for shared cars opens two completely new scenarios:

- “Shared” carsharing. Imagine that you open a carsharing app of the future and request a car. The app puts you in a waiting queue and says that the estimated waiting time for the next car is 30 minutes. But someone from the same street is going to the same part of town. The app offers to cut your waiting time to 15 minutes if you both share the same car. Since you don’t know the person, the app offers to increase security by enabling a video camera inside the car (it is there anyway, to check whether you left the car clean). You accept the pooled ride, but decline the camera option, as the other person’s profile is rated 4.5 stars. Your car is available in 15 minutes.

- “Premium” shared cars. Let’s say you are in a hurry and don’t want to use a carsharing company that tries to maximize car usage. You use a more expensive carsharing company that promises to have a car available in five minutes or the cost of ride is on them. You pay a premium to get somewhere faster. It’s a nice system, although I guess in some posh downtowns everybody will try to use the premium shared cars, in which case you are back to square one. Then you need a “super-premium” car share. Another option is existing car sharing companies adding surge pricing, but Uber showed that paying 4x more for basically the same service didn’t go well with the customers.

Rebirth of the parking space

If all that space becomes available, cities can reclaim it for public use. This is especially true in Europe, where cities were never designed for cars—to make room for them, something had to be given away. Year by year, streets have been made narrower by side parking, parks have been converted to parking, and new buildings have been constructed with large parking lots next to them. If the majority of the transportation burden falls to shared cars, buildings will just need a “valet” parking area in the front. The valet will not be a real person—but your smartphone.

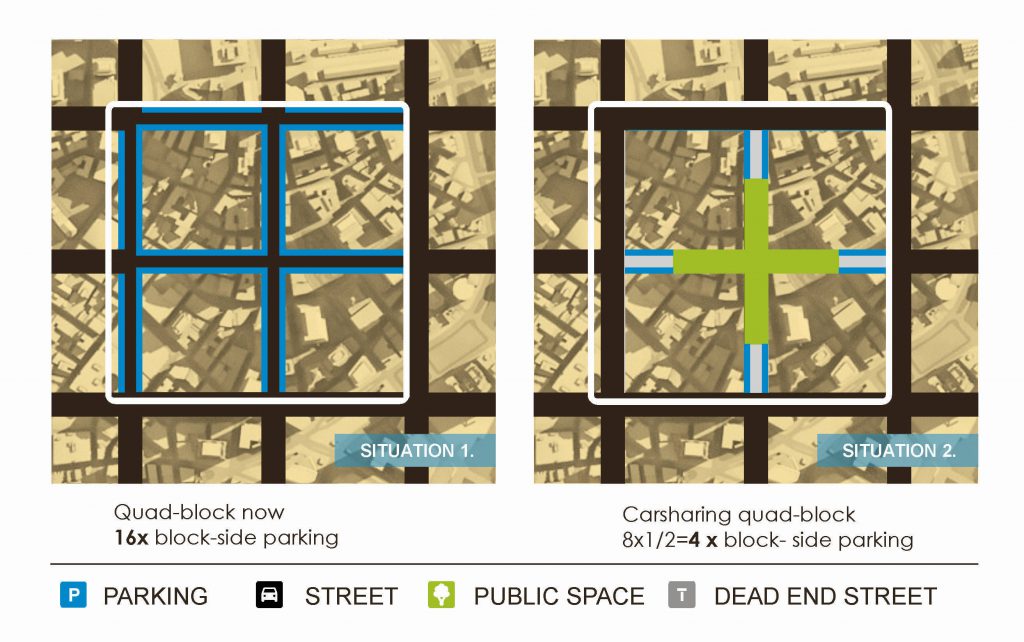

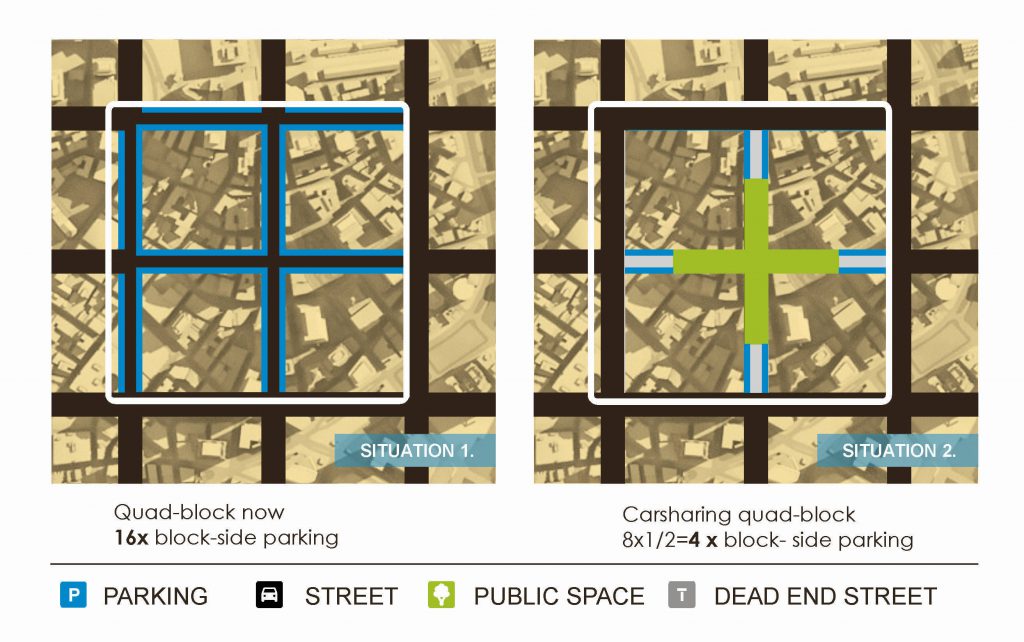

That could dramatically change suburban landscapes, where every business has it own large parking area. But even the dense city grid can be changed. For example, although Barcelona is known as a well-planned city, most streets today are taken by cars. People got excited a few weeks ago when a plan for “superblocks” was announced. The idea is to designate one-third of the streets as through roads, and two-thirds as pedestrian-friendly zones. The problem is that the second phase of the plan calls for elimination of parking in the pedestrian-friendly zone, by building off-street garages for every superblock. That is an enormous capital project for the city. With carsharing, the solution becomes easier:

- Make every second street a through street. Eliminate side parking in through streets to add two additional lanes of throughput.

- Make other streets half dead-end streets (used for parking of car shares), half pedestrian-only zones.

See the illustration below:

This solution builds on the existing infrastructure (no new garages are needed), and you get a mini city square in place of every fourth intersection. Side parking places are reduced 4x, which is achievable with carsharing. The longest walking distance to an available car is one block.

Think what all that change would mean for Los Angeles, for example. It currently has 200 square miles covered with parking lots, 1.4x more than the total land taken up by streets and freeways.

All that transformation would be powered by the simple idea:

The purpose of cars is to be driven, not parked.

The heroes of the future

Some people had seen the future long time ago.

Zipcar, Flexcar, and City Car Club were all started in 2000. But they missed the convenience of a smartphone.

In 2007, Steve Jobs announced the iPhone and, a few years later, ridesharing companies started popping up in San Francisco: Uber in 2009, Sidecar in 2011, and Lyft in 2012.

In 2010, car2go went public in Austin, Texas.

All those services were convenient and cheap, and big companies started paying attention.

In 2014, Sergey Brin said this of Google’s self-driving car: “So with self-driving cars, you don’t really need much in the way of parking, because you don’t need one car per person. They just come and get you when you need them.”

In 2016, Elon Musk unveiled his master plan, which states: “You will also be able to add your car to the Tesla shared fleet just by tapping a button on the Tesla phone app and have it generate income for you while you’re at work or on vacation.”

In 2015, even GM said: “We’ve come to the conclusion that our industry within the context of today’s traditional vehicles and today’s traditional business model is not sustainable in its current form.”

Brave words from an old school car maker! I would also consider innovative people at GM, Daimler, BMW, Ford, and VW to be heroes, although they mask really well under the grey suits.

But every story of heroes also has a story of…

The villains

Change management 101: When there is a big change, no matter how good, there is going to be someone opposing it. In this case, it seems that one of the villains are the people we elected to work in our interest.

The private car is not a fair competitor. Parking is subsidized by both the politicians and the average people. People want “free” parking, but do you really think that 16.8 m2 of valuable land in the city is “free”? It is not just taxpayers’ money. When you go to a McDonald’s, a parking fee is hidden in the burger price because the owner needed to purchase land for a parking lot. When you purchase a condo, the price is higher because the building developer needed to build underground parking.

The book The High Cost of Free Parking estimates that the total cost of “free” parking in the U.S. is 1-4% of the GNP. (I also highly recommend that you listen to the Parking is Hell episode of the Freakonomics podcast.) The economic price of monthly parking in big cities goes from $438 in Boston, to $719 in Rome, to a staggering $1084 in London.

What puzzles economists is simple math to politicians. Giving affordable parking to people gets them votes. My hometown of Zagreb has some great populists in power. As a city center resident, you can leave your piece of metal next to the parliament for the price of $15. Per month. For years I complained about the price of parking, but then I realized that maybe I should shut up.

If the price of parking were subject to market forces, math would be simple. Shared cars would spend less time parked and you would share the price of parking with other carsharing users. With private cars, it would be your sole responsibility to pay $500 per month for parking.

But a mayor who introduces an economic price of parking would soon be impeached. So maybe the real villain of this story is not the politician, but you, dear voter?

Conclusion

It seems that the future of urban transport is electric, self-driving shared cars. But that electric future requires new cars with great batteries, while self-driving cars are five years out. Both are going to be more expensive.

However, carsharing is already everywhere. There are rideshares like Uber and Lyft. You can convert your existing private car to a shared car with an electronics kit, such as the $99 Getaround Connect. With new legislation in the cities, which promotes the sharing of cars and doesn’t subsidize parking, we can have more liveable cities and better urban transport now, without large capital investments.

But for that, we need a change in mentality. If you agree with that, spread the word.

UPDATE: check discussions on Hacker News and Reddit.

Car2go decided to pimp up its rides, so now you can book a Merc:

Car2go decided to pimp up its rides, so now you can book a Merc: Citroen also decided to join the party. The company offers a fleet of mostly electric C-Zeros with

Citroen also decided to join the party. The company offers a fleet of mostly electric C-Zeros with  Volkswagen got angry that Mercedes and BMW were eating all the cake, so it purchased a

Volkswagen got angry that Mercedes and BMW were eating all the cake, so it purchased a  While Sixt is partnering with BMW, Hertz has its own

While Sixt is partnering with BMW, Hertz has its own  Don’t laugh at the idea of shared scooters. This is a cultural thing—while in the US, the ideal transportation vehicle is a sedan and in Europe a compact car, two billion people in Asia consider scooters a family transport solution. Look at this nice family in Vietnam:

Don’t laugh at the idea of shared scooters. This is a cultural thing—while in the US, the ideal transportation vehicle is a sedan and in Europe a compact car, two billion people in Asia consider scooters a family transport solution. Look at this nice family in Vietnam: And eMio is not the only one. Just

And eMio is not the only one. Just  Both Coup and eMio have an unusual charging solution: their teams go around the city and swap empty batteries for full ones.

Both Coup and eMio have an unusual charging solution: their teams go around the city and swap empty batteries for full ones.