Why read the Working Backwards book?

Amazon is not very popular right now, with many media criticizing its treatment of workers and its cut-throat culture. Still, love them or hate them, there are some undeniable achievements. Amazon is a tech giant with a market cap of over 1.4 trillion USD. For the first eight years, they operated with a loss as they reinvested all profits into expansion. To me, the most impressive thing about Amazon is that they succeeded in many different business fields. Other tech giants often have a primary business domain. E.g., Microsoft makes software, Apple premium consumer devices, and Facebook social media platforms.

But Amazon was revolutionary in all these fields:

- E-commerce: First online bookseller and one of the first online stores.

- E-commerce platform: Fulfillment by Amazon handles logistics for other sellers.

- Logistics: Amazon Delivery and Amazon Prime (with same-day delivery).

- Ebooks: Amazon Kindle, the most popular e-ink reader, and Kindle Library, the biggest ebook library.

- Cloud computing: Amazon Web Services (AWS), the first and largest cloud vendor.

- Voice assistants: Amazon Echo, the first voice assistant device.

- Video streaming: Amazon Prime Video and Amazon Studios.

- Consumer products: Amazon Fire tablet, Amazon Fire TV, and Amazon private labels

- Retail: Whole Foods Market (acquired) and Amazon Go, the first cashierless convenience store.

Notice that the above domains require completely different know-how and different business principles. E-commerce is a low-margin business, logistics involves a lot of low-skilled employees, and cloud computing requires a small number of high-tech employees. Amazon Studios is an entirely different creative business, with connections to Hollywood and high margins. Amazon Kindle, Echo, and Go required the invention of new technologies. How can a single company excel at all of that?

The book’s thesis is that Amazon excels in different fields because of its unique “Amazonian” culture.

Amazonian culture

Where does “Amazonian” culture come from? It is never directly stated in the book, but insider stories make it apparent that Jeff Bezos decides on Amazon culture. Jeff’s famous company-wide memos prohibit some practices and prescribe what to do instead.

On the one hand, that is expected. Amazon, in 2022, had 1.6 million employees. Without strong management at the top, Amazon’s culture would be a mish-mash of cultures new employees would bring. On the other hand, a strong man at the top goes against common advice from conferences and management books: empowering your employees, having a flat organization, and deciding on company culture together with employees. I found similarities between Jeff Bezos and Steve Jobs — you are free to do whatever you want in a company that is not Amazon. While Steve Jobs insisted on product excellence, Jeff Bezos insisted on following Amazon’s procedures and principles.

Here are the central tenets of the Church of Jeff Bezos, in no particular order.

Decoupled two-pizza teams

Again, this principle goes against common wisdom. Many consultants and books say “communication is key” and “communicate important things to all relevant people.” In practice, this turns into large group meetings and emails with a dozen recipients, so employees spend most of their time in meetings or reading emails.

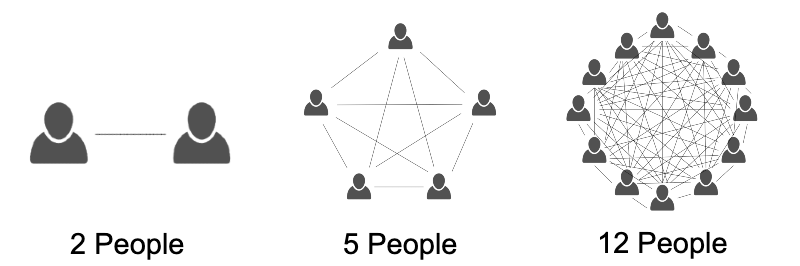

That is because the number of communication channels grows exponentially with the number of participants (a variant of Metcalfe’s law):

An example from the book is a minor change in the Amazon Affiliates program. At first, Amazon gave affiliate commissions only for directly linked products. They decided to expand that to all products purchased by affiliate visitors. It was a straightforward change, and they estimated it could be released in a month. However, they first needed approval from the database team to make changes to the central Amazon database. Then they needed to get the approval and materials from the marketing team. Then they needed to get approval from the legal team. Then they need to write support documents and instruct support agents. All relevant parties need to be synchronized on the release date. In the end, a change a few people could implement in a week took six months!

Jeff recognized these internal dependencies are why companies get slower as they grow. He proposed a radical solution: structure Amazon around independent “two-pizza” teams (below ten people). If the team can’t be fed with two pizzas, it should be broken down. Each team has the resources and authority to release a feature without waiting for other teams. A team should expose their feature as an internal API and document how to use it. In the above example, the affiliate team should not depend on the database team to release a new version. There should be separate affiliate API and database API, with separate release schedules and documentation. If one team needs a meeting or written approval from another team to release a feature, that is a failure of an organization.

But what if a change from one team breaks something or causes a problem? That can happen, but Jeff says breaking changes are not a problem if the change is reversible. Most tech problems can quickly be reverted, e.g., a problematic new feature can be disabled. Company coordination between many teams is needed only when the change is not easily reversible, e.g., shipping faulty devices to customers.

This is not how most companies operate and it is hard to implement. Bosses like to retain political control over many people and don’t like independent teams doing stuff without their knowledge. Developers don’t like writing internal documentation or exposing API when it takes less time to connect to a central database. And why write internal documentation when a coworker can ask you over the phone, email, or in a meeting?

At Amazon, you need to do it because Jeff said so. And Jeff did such a good job breaking Amazon’s monolith into independent teams that he realized Amazon could expose internal APIs and documentation as public cloud services. That is how Amazon, then an e-commerce company, became a cloud computing vendor. In Q4 2021, Amazon Web Services generated 13% of Amazon’s revenue but 100% of Amazon’s profits (other divisions reinvested all profits).

Notice that the “two-pizza teams” principle is similar to the “move fast and break things” idea. In both cases, it is more important to move fast, even with occasional problems, because most problems can quickly be fixed.

Six-page memos

In Jeff’s words, “Six-page memos are the smartest thing we ever did.“

In the beginning, Amazon used the same meeting structure as other companies:

- A meeting organizer would prepare PowerPoint slides.

- While slides were presented, meeting participants could interrupt and ask questions.

- A meeting would end with a discussion and decision on future actions.

By 2004, Jeff started to hate this structure. On a plane, he had read a 25-page paper, The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint, which explained that bullet points are a terrible way to structure arguments. That paper proposed banning PowerPoint in organizations and using written text instead. The paper had such an influence that Jeff immediately sent an email banning PowerPoint and mandating narrative memos instead. In Jeff’s own words, “writing a good 4-page memo is harder than ‘writing’ a 20-page PowerPoint because the narrative structure of a good memo forces better thought and better understanding” and “If someone builds a list of bullet points in Word, that would be just as bad as PowerPoint.” In other words, bullet points are lazy thinking.

That directive was met with strong resistance at Amazon. PowerPoint was standard, and making slides was easier than writing narrative memos. Memo needs to stand on its own, as there is no presenter who can explain bullets or who you can ask for clarification. For many managers, this seemed like an overly academic approach. But Jeff insisted.

From then on, meeting organizers would prepare a six-page memo they would not distribute in advance. Instead, all participants would get and read the memo in the first 20 minutes of a meeting in complete silence. This solves a few problems:

- Preparation: With silent reading at the beginning, all participants are on the same page. Before, people who prepared or read meeting documents in advance had an advantage in the discussion.

- Text limit: Because reading is limited to 20 minutes, a memo can’t be longer than six pages. Tricks to cram more text, like using smaller fonts or margins, make no sense with a 20-minute limit.

- Shareability: A memo is standalone and can be shared with people outside the meeting. That doesn’t work with slides, as they depend on a presenter explaining them.

After reading (Jeff would often finish reading the last), participants would discuss and decide on the next steps.

It took some time for six-page memos to become part of Amazon’s culture. When it did, memo writing became competitive. The best writer on the team would produce a memo, and other team members would criticize it. The book mentions that successful six-page memos were distributed around the company as examples, and writing well became a vital skill at Amazon.

Working backwards

Once two-pizza teams are formed, and the new project is defined in a six-page memo, what is the next step? A usual corporate product development process would start with implementing the product, then creating marketing materials, and ending with a press release and support documents.

Jeff Bezos noticed problems with that order:

- It is company-centric to start with development first. In the development phase, a company is inclined to cut corners and reuse existing solutions that are not optimal for customers.

- Project goals are not clear to all employees involved. Even developers are not always clear on which features are necessary and which are optional.

- The product team often develops features that the marketing team doesn’t find marketable, and lacks features that would be great for marketing.

- If the price is left unspecified, the product team will often create a product that is too expensive.

Instead, the process should be customer-centric and start with customer needs. Jeff asked teams to work backwards, starting from a target customer. The first thing a team needs to create is a press release for the fictitious product. Industry practice is that press releases should be 300-400 words, not longer. Since that limits a product description, only key features can be listed. A press release also explains use cases, target customers, price, and availability. After approval by management, the entire team reads it and knows what they are working on. The next thing developed after a press release is an internal FAQ (frequently asked questions) that explains all things team members need to know but are not in the press release, for example: which services, resources, or hardware is required, people involved, minor features, architecture, timeline, budget, edge cases, etc. The purpose of the FAQ is that all team members understand the details and commit to it. After the FAQ is approved, product development starts.

An example given in the book: when Kindle 2 was being developed, Jeff insisted that the press release includes “Whispersync.” Whispersync is an ability to wirelessly sync books, bookmarks, and reading progress over a GSM network. Previously, customers needed a cable, a PC, a sync application, and an internet connection to move books to Kindle. With Whispersync, purchased books would magically appear on your Kindle after a purchase. And the fictitious press release stated Whispersync will be free with every Kindle. Jeff and the marketing team loved it. The internal FAQ explained that Whispersync will use Whispernet, Amazon’s custom always-on 3G connection. That put a great burden on the product team. They needed to add a 3G modem, negotiate prices with network carriers to have an affordable 3G plan, incorporate the cost of 3G in the price of Kindle and books, and develop new syncing software. If the press release didn’t insist on that feature, employees would be inclined to do what is easiest for them: keep the existing cables and sync software. The fictitious press release made solving that customer pain point obligatory. When Kindle 2 was released, journalists were delighted to discuss the revolutionary Whispersync feature.

Measure input metrics, not output metrics

Companies often focus on what Jeff calls “output metrics”: revenue, profits, stock price, market share, etc. They are “output” because they result from many input metrics, some of which we don’t control. For example, revenue depends on the current economy and seasonality, stock price depends on bear and bull markets, and market share depends on competitors. It is silly to be proud of increased monthly revenue if it was caused by holiday season shopping. It is silly to be proud of the increased stock price if lower interest rates drive it, not your actions.

Jeff says that the primary metrics should be “input metrics” that you have direct control over. In the case of Amazon, input metrics are inventory size, prices, delivery times and prices, etc. If you have a large inventory, low prices, and fast and affordable delivery, then the output metrics like revenue will be good. It is the management responsibility to decide which input metrics are the right ones.

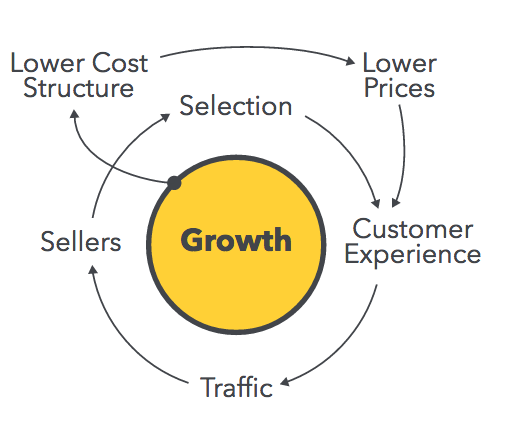

Jeff believes the right product metrics make the growth flywheel spin faster. Amazon’s e-commerce growth flywheel is below:

Metrics that Amazon has control over (and are good input metrics) are product selection, prices, and customer experience (which includes delivery experience, website experience, refund experience, etc.).

However, it is more complex than given in the above diagram. The book provides an example of how in the early days, Amazon’s input metric was the “number of product detail pages.” However, then they noticed that an increase in the number of listed products didn’t cause an increase in revenue. It turned out that the inventory team added many products that were not popular, were out of stock, or had a long shipping time. They changed the input metric to “number of product page views X percentage of items in stock that can be shipped immediately,” which accounts for both product popularity and inventory. But, the book advised against having too complicated or too many input metrics. One department had many complex input metrics, resulting in employees not understanding how to influence them. They switched to simpler metrics, so everybody could understand how to contribute to the bottom line.

Single-threaded leadership

Companies always have a shortage of good managers to lead new projects. As a result, managers often need to manage multiple projects. That is bad. The best way to make a project fail is to give it to someone “30% of their time.” If the project is important, it deserves complete focus from a manager and a team. The book gives examples of times when Jeff moved heads of highly successful divisions to work on new things that made no revenue for years. Some managers thought they were being demoted by working on unprofitable projects, only to achieve wild success after a few years.

In Amazon’s terminology, single-threaded leadership is having a single-threaded owner heading a single-threaded team; both focused on the new project alone. Without dedicated focus, employees would revert to doing legacy work, as legacy work is bringing money.

Bar raiser for hiring

At the beginning, Amazon had a high hiring bar because Jeff Bezos had very high expectations. As the company grew, they noticed that the quality of new hires varied widely. That was mostly caused by the urgency bias — a candidate who was a poor fit still got hired because there was an urgency to fill their position. A new employee often didn’t match the expectations and left after a short period, returning the company to square one.

Even without urgency bias, new employees’ quality varied depending on who interviewed them and which process they used. For example, Jeff preferred candidates who excelled at academia, even if that was not necessary for their work. Other interviewers had lower criteria, did unstructured interviews, or asked questions that didn’t predict future performance. If one interviewer was against the hire, they were still inclined to approve it if other interviewers were eager to hire.

To improve hiring, Amazon found and trained internal “bar raisers.” A bar raiser is an employee outside a team who comes as an objective 3rd party to check if a new hire satisfies minimum hiring standards. They checked the procedure was followed, structured interviews were done, and that each interviewer voted “hire” or “no hire” in writing. Each interviewer needed to write their opinion before final approval, without knowing what other interviewers thought.

Conclusion

I really enjoyed reading this book. No matter what I think of Jeff Bezos, I like his ideas on how to organize a large corporation to behave like a startup. If you share the same sentiment, get the book in Kindle, audiobook, or paper format (I don’t earn a commission):

Working Backwards book on Amazon