These rules are not new, and they are not mine; I stole them from Andrew Ng and Benedict Evans, two men with a huge following. Still, a large majority of AI entrepreneurs and engineers don’t pay attention to them, maybe because these rules show why their AI project will fail.

AI’s Law of Diminishing Returns

To paraphrase Andrew’s words from Coursera’s Deep Learning Specialization course:

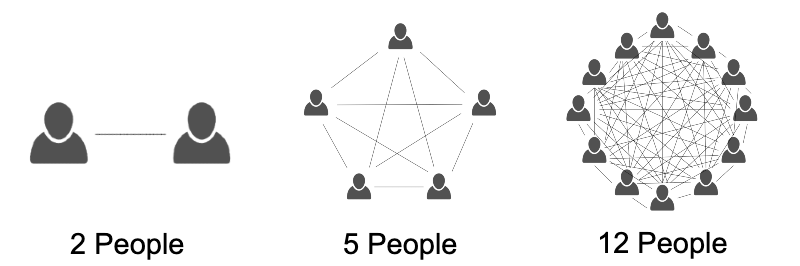

The effort to half an AI system’s error rate is similar, regardless of the starting error rate.

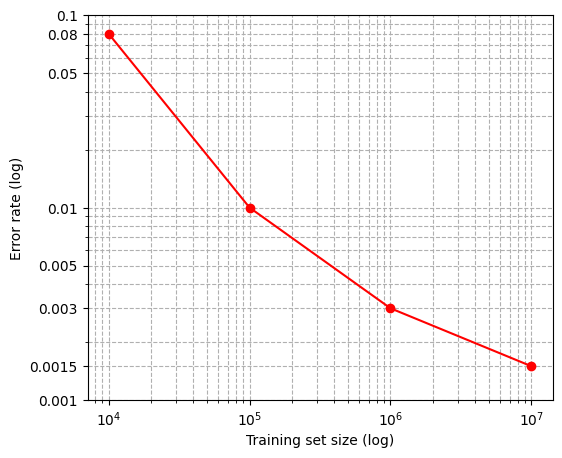

This is not very intuitive. If an AI system passes 90% of test cases and errors on 10%, then you are 90% done, right? Fix the remaining 10% of errors, and you will have 100% accuracy? Absolutely not. If it took you six months to halve the error rate from 20% to 10%, it will take you approximately another six months to halve 10% to 5%. And another six months to halve 5% to 2.5%. Ad infinitum. You will never achieve a 0% error rate on a real-world AI system. For an illustrative example, see this typical chart of error rate vs the number of training samples:

Notice that later in the training process, training set size increases exponentially with each error rate halving, and the error rate never reaches zero. Sure, you will get more efficient with acquiring training data (e.g., by using low-quality sources or synthetic data). Still, it is hard to believe that acquiring 10X more data is going to be much easier than acquiring the initial set.

This rule becomes more intuitive when dissecting what an AI system error rate represents: uncovered real-world special cases. There are an infinite number of them. For example, one of the easiest machine learning (ML) tasks is classifying images of dogs and cats. It is an introductory task with online tutorials that get 99% accuracy. But solving the last 1% is incredibly hard. For example, is the creature in the image below a dog or a cat?

It is Atchoum the cat, who rose to fame because half of humans recognized him as a dog. The human accuracy on dog/cat classification within 30 seconds is 99.6%. A dog/cat classifier with less than a 0.4% error rate would be superhuman. But it is possible. A training set with hundreds of thousands of strange-looking dogs and cats would teach a neural network to focus just on details encoded in dog or cat chromosomes (e.g. cat eyes). However, building such a dataset is orders of magnitude more complex than a tutorial with 99% accuracy. Other problems lurk in that 1% error rate: photos that are too dark, photos in low resolution, photo compression artifacts, photo post-processing by modern smartphones (adding of non-existing details), dogs and cats with medical conditions etc. The problem space is infinite. This is still considered a solved ML problem though, because a 1% error rate is low enough for all practical purposes.

But for some problems, even a 0.01% error rate is not satisfactory, for example: full-self driving (FSD). Elon Musk said in a 2015 article with Forbes:

“We’re going to end up with complete autonomy, and I think we will have complete autonomy in approximately two years.”

Tesla was so confident in that prediction that they started selling a full self-driving add-on package in 2016, and they weren’t the only ones. Kyle Vogt, CEO of Cruise, wrote a piece called How we built the first real self-driving car (really) in 2017, in which he claimed:

“the most critical requirement for deployment at scale is actually the ability to manufacture the cars that run that software”

So, the software and the working prototype are done; they just need to mass-produce “100,000 vehicles per year.”

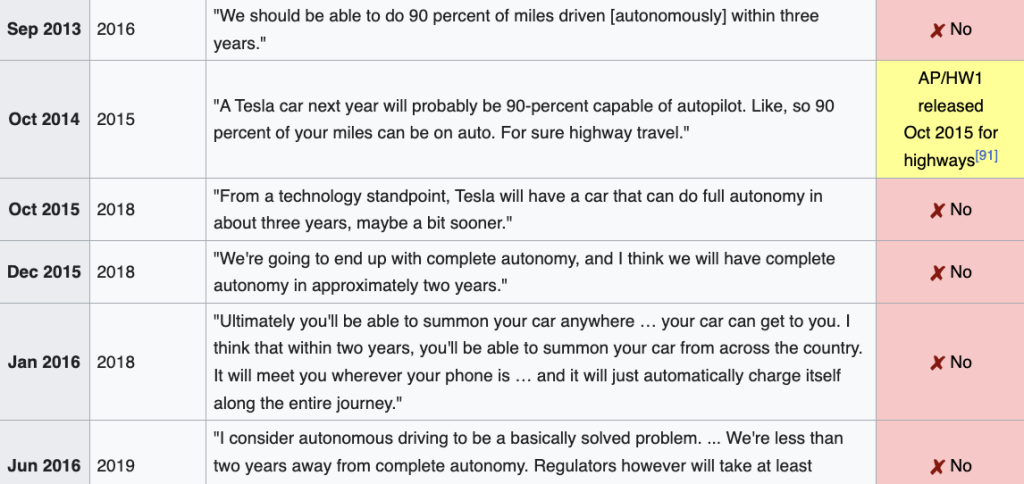

Fast forward to 2024. Elon Musk’s predictions for autonomous Tesla vehicles deserved a lengthy Wikipedia table, mostly in red:

What about Kyle Vogt? In October of 2023 Cruise’s car dragged a pedestrian for 20 feet, after which California’s DMV suspended Cruise’s self-driving taxi license. Kyle “resigned” as CEO in November 2023.

Don’t misunderstand me—I believe autonomous cars will have a significant market share, probably in the next decade. The failed predictions above illustrate what happens when entrepreneurs don’t respect the AI law of diminishing returns. Elon and Kyle probably saw a demo of a full-self driving car that could drive on its own, on a sunny day, on a marked road. Sure, a safety driver needed to intervene sometimes, but that was only 1% of the drive time. It is easy to conclude that “autonomous driving is a solved problem,” as Elon said in 2016. Notice how ML scientists and engineers didn’t make such bombastic claims. They were aware of many edge cases, some of which are described in crash reports. Edge cases include:

- A pedestrian crossing a two-lane avenue with a bicycle at night and without lights (2018 Uber crash).

- The lane’s white lines diverging before a barrier (2018, Tesla Model X crash).

- A white trailer truck against the white sky (2019 crash, Tesla Model 3 decapitated the driver and continued driving for 40 seconds).

- A vehicle kicking a pedestrian under an FSD car (2023 Cruise incident mentioned above).

Why so many companies promised a drastic reduction in self-driving error rates in such a short time without having a completely new ML architecture is an open question. Scaling laws for convolutional neural networks have been known for some time, and the new transformer architecture obeys a similar scaling law.

AI’s Product vs Feature Rule

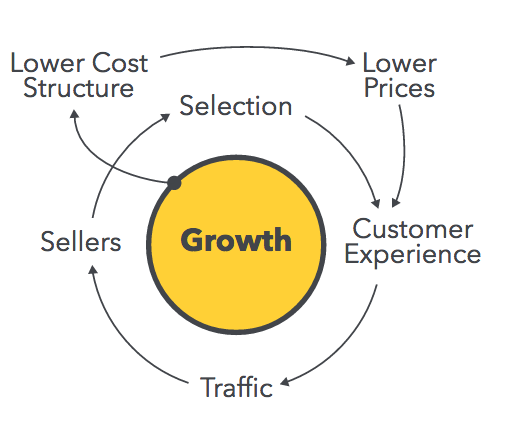

When is an AI system a good stand-alone product, and when is it just a feature? In the words of Benedict Evans from The AI Summer podcast: “Is this feature or a product? Well, if you can’t guarantee it is right, it’s a feature. It needs to be wrapped in something that manages or controls expectations.” I love that statement. The “it is right” part can be broken down using error rate:

If your AI system has a higher error rate than target users, you have an AI feature in an existing workflow, not a stand-alone AI product.

This rule is more intuitive than the law of diminishing returns. If target users are better at a task, they will not like stand-alone AI system results. They could still use AI to save them effort and time, but they will want to review and edit AI output. If AI completely fails at a task, humans will use the old workflow and the old software to finish the task.

Let’s take MidJourney for example, which generates whole images based on a text prompt. When I used it for a hobby project last year, satisfying artistic images appeared instantly, like magic. But then I spent hours fixing creepy hands, similar to the ones below:

Each time MidJourney created a new image, one of the hands had strange artifacts. Finally, it generated an image with two normal hands—but then it destroyed the ears in another part of the image. The problem was less with wrong details and more with bad UI, which didn’t allow correction of the AI’s mistakes.

Adobe’s approach is different—it treats generative AI as just one feature in its product suite. You use an existing tool, select an area, and then do a generative fill:

|  |

You can use it for the smallest of tasks, like removing cigarette butts from grass in a wedding photoshoot. If you dislike AI grass, no problem—revert to the old designer joy of manually cloning grass. Also, Adobe Illustrator has generative Vector AI that generates vector shapes you can edit to your liking.

MidJourney makes more impressive demos, but Adobe’s approach is more useful to professional designers. That doesn’t mean MidJourney doesn’t make sense as a product, its target users are the ones who don’t care about details. For example, last Christmas, I got the following greetings image over WhatsApp:

Did you notice baby Jesus’ hands and eyes? Take another look:

That would never pass with a designer, but that is not the point. There is a whole army of users who don’t care about image composition and details, they just want images that go with their content. In other words, MidJourney is not a replacement for Adobe’s Creative Suite—it is a replacement for stock photo libraries like Shutterstock and Getty Images. And judging by the recent popularity of AI-generated images on social media and the web, people like artsy MidJourney images more than stock photos.

Low-hanging fruit in stand-alone AI products are use cases where a high error rate doesn’t matter or is still better than the human error rate. An unfortunate example is guided missiles; in the Gulf War, the accuracy of Tomahawk missiles was less than 60%. But the army was happy to buy Tomahawks because they were still much more accurate than older alternatives, as fewer than 1 in 14 unguided bombs hit their targets.

Evaluating startups based on the above rules

The great thing is that error rates are measurable, so the above rules give a framework to judge an AI startup quickly. Below is a simple startup example.

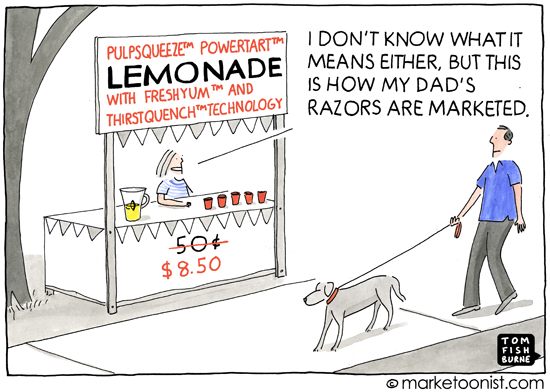

Devin AI made quite a splash in March of 2024 with a video demo of developer AI that can create fully working software projects. The announcement says that Devin was “evaluated on the SWE-Bench” (relevant benchmark), and “correctly resolves 13.86% of the issues unassisted, far exceeding the previous state-of-the-art model performance of 1.96% unassisted.” So, the current state-of-the-art (SOTA) has a 98% error rate, and they claim to have an 86% error rate. Even if that claim is valid (it wasn’t independently verified), why do their promo videos show success after success? It turns out that the video examples were cherry-picked, the task description was changed, and Devin took hours to complete.

In my opinion, Microsoft took the right approach with GitHub Copilot. Although LLMs work surprisingly well for coding, they still make a ton of mistakes and don’t make sense as a stand-alone product. Copilot is a feature integrated into popular IDEs that pops up with suggestions when they are likely to help. You can review, edit, or improve on each suggestion.

Again, don’t get me wrong. I think coding SOTA will drastically improve over the next few years, and one day, AI will be able to solve 80% of GitHub issues. Devin AI is still far away from that day, although the company has a valuation of $2 billion in 2024.

More formally, the framework for evaluation is:

- Find a relevant benchmark for a specific AI use case.

- Find the current state-of-the-art (SOTA) error rate and human error rate on that benchmark.

- Is the SOTA better or comparable to the human error rate?

- If yes (unlikely): Great, the problem is solved, and you can create a stand-alone AI product by reproducing SOTA results.

- If no (likely): Check if there is a niche customer segment that is more tolerant of errors. If yes, you can still have a niche stand-alone product. If you can’t find such a niche, go to the next step.

- You can’t release a stand-alone AI product. Wait for SOTA to get better, pour money into research, or go to the next step.

- Think about how to integrate AI as a feature into the existing product. Make it easy for users to detect and correct AI’s mistakes. Then, measure AI’s return on investment:

AI_ROI = Effort_saved_by_AI / Effort_lost_correcting_AI

If too much user time is spent checking and correcting AI errors (AI_ROI<=1), you don’t even have a feature.

Or, to summarize everything discussed here in one sentence:

Every innovative AI use case will eventually become a feature or a product, once the error rates allow it. If you want to make it happen faster, become a researcher. OpenAI’s early employees spent seven years on AI research before overnight success with ChatGPT. Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI’s chief scientist, still didn’t want to release ChatGPT 3.5 because he was afraid it hallucinated too much. Science takes time.

If you found this article useful, please share.